In Indian Hindu mythology, there is a famous story about the infant Lord Krishna. His mother, Yashoda, wrongly accuses and scolds him for eating dirt. Yasoda asked Krishna to open his mouth. She sees in Krishna’s mouth the whole complete entire timeless universe. Yasoda sees stars, planets, all emotions, herself, three forms of matter, creatures, villages, and every tiny thing that can exist. Overwhelmed and breathless, she asked Krishna to close his mouth.

The interpretation of this story has a different dimension in Hindu mythology. I have observed similarities with our modern-day scientific facts on our oral cavity.

The Oral Microbiome

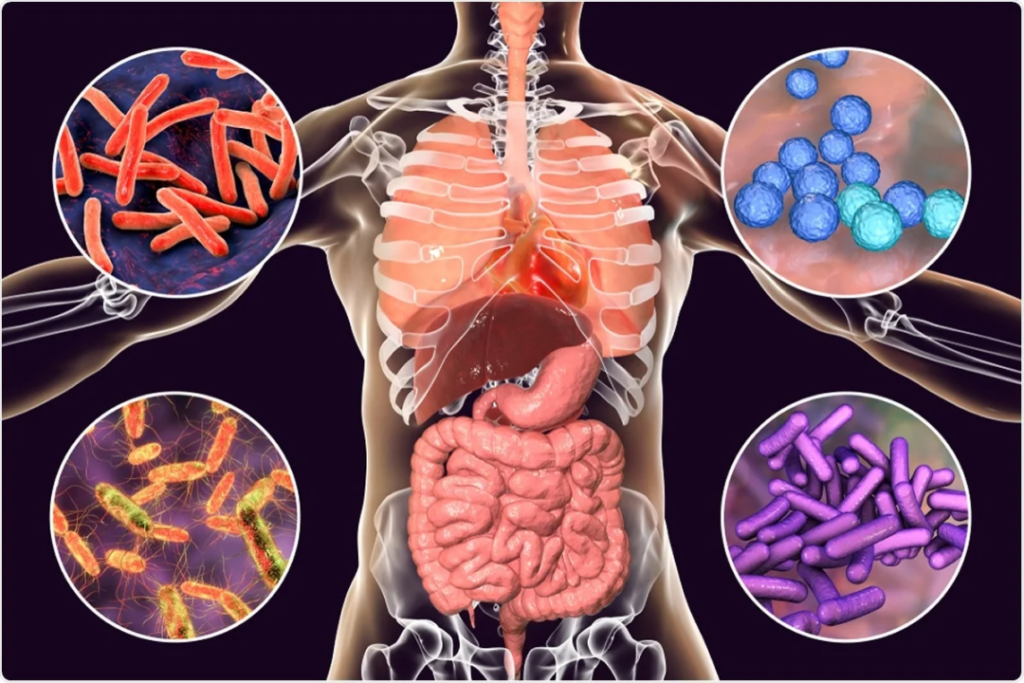

The oral cavity is the gateway to the human system. It presents approximately 700 species of microorganisms. The common bacteria present in all sites of a healthy

mouth are Streptococcus, Gemella, Veillonella, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, Actinomyces, and Prevotella.

The oral cavity has different areas – hard palate, soft palate, gums, tonsil, tongue etc. Each of these areas has a well-differentiated bacterial composition plus the common ones.

Looks quite similar to the picture of mythological story of Krishna… right?

What could be the possible reason for these different niches?

There may be several factors. pH, salinity, redox potential, oxygen, nutrition and dental hygiene are the key players in the bacterial niche differentiation.

The Gut Microbiome

Gut and oral microbiomes are the two largest microbial ecosystems in the human body. The human gut harbours the largest and the most well-characterized microbial ecosystem in the human body.

It has 500 – 1000 species in more than 50 different phyla!

Are oral cavity and gut microbes connected?

Anatomically, the entire human gastrointestinal (GI) tract looks like a hollow tube. It begins at the mouth and ends at the gut (anal opening). Moreover, both sites are also chemically connected since saliva and digested food pass through the GI tract.

Despite this connectivity, the oral and gut microbiomes are highly diverse. They show unique signatures distinguished from each habitat.

Source: Nationwide Children’s Hospital

What are the pathophysiological functions of these microbes?

The gut microbial community regulates metabolic pathways and immune responses of our body.

These microbial cells express molecules known as microbial-associated molecular patterns and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Receptors (pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in our cells interact with these molecules. This microbial–host interaction can stimulate the immune system and inflammatory responses inside our body.

Thus, any alteration to these gut microbial communities (dysbiosis) can cause numerous human diseases – from infectious diseases to Alzheimer’s disease.

The oral cavity is the second-largest microbial habitat inside our body. Our knowledge is still less to fully understand the implications of the oral microbiome in human health.

The oral microbiome is directly associated with dental health. A few examples of microbes causing oral diseases are:

- Streptococcus mutans for dental caries

- Porphyromonas gingivalis for periodontitis

- Fusobacterium in oral cancer (oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC)

The oral microbiome can affect systemic health conditions. Several experimental pieces of evidence support that oral dysbiosis is closely associated with systemic diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

Oral microbiota can translocate to the other organs. Oral dysbiosis can induce the production of PAMP signals ( lipopolysaccharide; LPS).

These signals stimulate systemic innate immune responses and inflammatory transcription factors (e.g., nuclear factor κB).

These are one of the primary mechanisms underlining that the oral microbiome regulates pathogenesis in distal organs.

What is the interconnection between Oral and Gut Microbiomes?

The oral–gut barrier keeps the microbiomes well-segregated. The oral microbes have to cross the physical distance and the chemical hurdles, such as gastric acid and bile.

However, the impairment of the oral–gut barrier can allow interorgan translocation and communication. For instance, patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) had a significant increase in Haemophilus and Veillonella in the gut mucosa. Both of these are common oral commensal microbes.

Gut microorganisms may be transmitted to the oral cavity by faecal-oral routes. It can occur through direct contact and indirect exposure to contaminated fluids and foods.

This bidirectional interaction is known as the oral-gut microbiome axis. It can mutually shape and reshape the microbial ecosystem of both habitats. Thus, they can finally modulate physiological and pathological processes in our bodies.

Source: doi.org/10.3390/cancers1302124

The human gut microbiome profiles can change

depending on health status, environmental

factors, genetics, and even lifestyles.

How do these pieces of information help in cancer diagnosis?

The second leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide is Colorectal cancer. Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) is the most well-established risk factor for the development and progression of colorectal cancer.

IBD represents chronic inflammatory disorders of the colon and small intestine, including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).

In a healthy gut, the mucosal barrier remains intact. So the gut microbiome is barely invaded and colonized by microbes derived from other habitats. However, in IBD patients, the mucosal barrier is impaired. It causes increased gut epithelial permeability. Surprisingly, oral-resident bacterial strains are isolated from the gut microbiome of IBD patients. It is possibly due to gut leakiness.

Let us take one example to understand.

Fusobacterium nucleatum resides commonly in the oral cavity but rarely in the guts of healthy individuals. Interestingly, IBD patients showed colonization of F. nucleatum in the gut, which was more invasive than other F. nucleatum strains, indicating the presence of the oral–gut microbiome axis in IBD patients.

Source: Microbwiki

Reports also mention that F. nucleatum can co-aggregate and co-infect with the oral pathogen P. gingivalis. Several studies have shown that P. gingivalis invaded colorectal cancer cells and promoted cancer cell proliferation. It indicates the involvement of periodontal pathogen in colorectal tumour progression.

Oral microbiome changes are associated with the risk of GI cancer. It can be a potential index for early detection.

Oral and gut microbiome data can significantly increase the sensitivity to predict and detect polyps or tumours in colorectal cancer. Moreover, the modification of the oral microbiome by improving dental hygiene and supplementation with probiotics may also modulate the pathogenesis of the disease.

Can the gut microbiome and the oral

microbiome together be a diagnostic or

prognostic tool and a therapeutic target for

cancer?